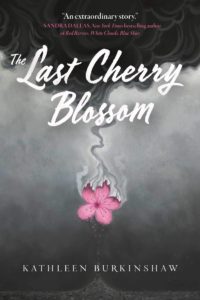

In this episode of the Books on Asia Podcast, sponsored by Stone Bridge Press, host Amy Chavez talks with Kathleen Burkinshaw in the U.S. about her book The Last Cherry Blossom, and about hibakusha, the Japanese word that refers to victims of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki that ended WWII.

Podcast 17 Show Transcript:

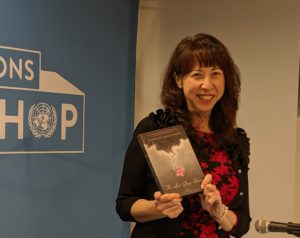

Amy Chavez: Well, I just want to let you know that I feel like I’m talking to Superwoman here. You’re an author, you’re a speaker, your book has won several awards. You’ve talked at the United nations in 2019, you’ve been on NHK and you talk to schools. It’s just really a pleasure to be able to talk to you today about, of course, your book, The Last Cherry Blossom, which has just recently come out on audio as well.

And, we’re also looking forward to hearing your mother’s story about being a hibakusha, which is those people in Japan who were exposed to the atomic bombs in Nagasaki and Hiroshima. So can you tell us a little bit about your mother.

Kathleen Burkinshaw: My mother was 12 and a half when the bomb was dropped. She grew up in Hiroshima and she was about two miles away from the epicenter, a little bit less than two miles. So the journey of the book is kind of how I found out about my mother’s story because I did not know she was from Hiroshima until I was 11. She had always said Tokyo. And it was only because that summer she had those horrible, well, she always had horrible nightmares, but August was really bad.

And she finally broke down and told me that she was actually born in Hiroshima, but she lost her home and her family and her friends to the atomic bombing. And at that point she said she couldn’t tell me anything more. It was still too painful.

And then she said, “Don’t tell anyone.” So, it was really interesting because I didn’t really know what she may have gone through until I was in high school. That’s when we read John Hershey’s book Hiroshima. And that was really like my first idea of the horror that she had witnessed.

I still remember this moment and I ran into the room and I said, Is it as awful as this book is saying? And she wouldn’t even look at the book. She just said, “Words written cannot tell you how awful it was.” And I felt so sad for her. I felt so, upset for her. And you know, it’s really interesting because then she said to me, “Don’t tell your teacher because I can’t go in and talk about it. Don’t say anything.” So really between the time of high school and through college, she didn’t really tell me very much of what happened. I heard a lot about when she grew up, she had a lot of happy memories before she was 12 and being with her grandfather and how important he was to her and her friend Machiko, but it wasn’t until I was 30 when she actually told me what happened. And the main reason I think she did that was I had been very sick and I was hospitalized for over a month. And, when I finally got out of the hospital, I needed someone to help take care of me. My daughter was four then and my husband worked during the day. So my parents came and I was then diagnosed with Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy and that’s a chronic neurological, progressive pain disease. And it affects your sympathetic nervous system as well as your immune system. And the doctors had said that the deficiencies in my immune system, because of my mother’s exposure to the radiation, is one of the reasons why I ended up with this disease.

And it was really hard because I felt bad for my mom because she felt guilty. She shouldn’t have felt guilty, I didn’t blame her for anything, but she did. I had a career where I did healthcare contracts with hospitals and doctors. I wasn’t going to be able to continue. I knew that I wouldn’t walk unassisted again, and that it would eventually affect my hands, and both my legs.

And I had a four-year-old and so I became very despondent. I just didn’t know how I was going to keep going. And my mother started to tell me what she went through. And as she talked about those days, then she said to me, “I wanted to kill myself when I lost everyone and everything. And I didn’t, and I’m so glad that I didn’t because I have you and now I have Sarah,” my daughter, her granddaughter.

And she said that, I had the same samurai blood flowing through my veins and I would find the strength and I’d find my own way, differently, but I would find it and, you know, I always thought when she was telling me what she told me was helpful for her, but, you know, it was like what a mom does for your child, when you see them hurting and for her to actually do that for me was such a gift.

And I try not to talk about it too much because then I was in and out of the hospital for the next few years. My daughter doesn’t really remember me without needing a cane or a walker or a wheelchair, depending upon how I’m doing. When my daughter was in seventh grade, she had come home and she had said to me, she was very, very upset and she said, you know, we ended our social studies unit today on World War Two. And they had a picture of the mushroom cloud and these kids were talking about how cool that picture looked. And she said, can you go talk to them about who was under those mushroom clouds that day? Like Grandma. And that’s when I called my mom because I still hadn’t spoken about it anywhere. And I wasn’t sure what she was going to say.

Well, Sarah made the call. And because I really feel that part of it was that my daughter asked her and she was the only grandchild, and I think my mom would’ve done anything for her, but then when she spoke to me and said, yes, she said, “You know, those kids are going to be about the same age that I was. Between 12 and 13. And maybe because of that, they’ll relate to my story of being, a 12 year old and dealing with family issues and then having something like the bomb being dropped like that, and they’re all going to vote some day. So they can leave there knowing, nuclear weapons should never be used again.”

And that’s really what started the journey with everything. I spoke to schools for probably a good three years before I started working on a book. and it was interesting because one school had me, then other schools had invited me and then they asked, you know, is there anything for our curriculum because we don’t have anything on the Pacific’s side.

And that’s when I remember calling up my mom and telling her, you know, I had taken notes for Sarah to have some day, but I said, I think I will add some to this. And she said to me, “I can’t believe they’d really care what happened to a little girl in Hiroshima.” And she was just amazed at that. And in a few days I received this package from her and it was a copy of a picture of my mom and her papa.

And that always had a special place of honor in our home. And when, I saw that I knew she had more than just the horror that day that she lost everything. She had happy memories, she had loving memories and I really wanted to be able to show that as well. And, so talking with my mom, trying to find out what happened during those days, what happened that led up to those days, was really building a closeness in us that we didn’t have before, and so for her to be able to do that for me, and I know it was painful for her. It’s hard for me because when I do readings for schools, I hear my mother’s voice.

I still hear it as she was telling it, how she spoke about it all the way through till she was in her eighties. And these were nightmares that she had all the way through until her eighties when she passed away and so for her to be able to give that to me, and for me to then try to tell her story of how, you know, the coincidences that she had, her father, her Papa used to be at home in the morning and in the afternoon he’d go to the newspaper office but that day he went into town early to the train station so he could purchase a ticket for one of his employees so that person could then go, further north in Japan to see his injured son. And so that put him in the center of town. Her classmates were all in the center of town taking down the wooden buildings. But she didn’t go to school that day because she had been sick over the weekend. So her Papa said, you can take another day and you can rest. And then tomorrow you’ll join your classmates. And she said those two coincidences changed everything. within an instant for her, she’s outside talking with her best friend and then all of a sudden she hears an air raid siren, but she sees a weather plane and they keep talking and then she sees another plane. And she said, her hair literally did feel like it was up the back of her neck and she felt like this electric shock kind of feeling.

And then all of a sudden, it’s this bright white flash of light and this loud thunderous noise. And, you know, she’s clinging to her best friend, but then minutes later she’s covered in debris and her best friend is no longer right next to her anymore. She could hear her, but she couldn’t get to her. And she couldn’t quite figure out what was happening, whether it was an earthquake, whether it was, an actual bomb. And she would try to get her way out of there but every time she did stuff would fall. And so she was trying to wait a little bit, and then she heard a voice outside calling and it was her stepmother.

That’s when her stepmother said, you need to be digging from the inside and I’ll pull away stuff out here. And my mom was so afraid and, and she didn’t want to leave her friend. And she said, you can reach your friend much quicker if you’re on the outside. And that was the only thing that really pushed her to do that and she says, I’ll never forget to look at my street. And there was nothing on the street. Her houses were gone. It was dark, it was a weird lights in the sky, colors. And, she said, then I looked off in one area and just all I could see, it looked like tornadoes of fire and she knew her Papa was there.

But she wanted to get her best friend out. And so she’s trying to dig and unfortunately, you know, she never did get to her friend because they started to feel these raindrops and they were black and they thought it was oil, you know, that might burn them further. So her step-mother picked her up and went running to find shelter.

Then my mother passed out and the next time she woke up, it was time to look for her papa, but she never saw her friend again and, she always said, you know, it was just strange that you don’t think how quickly your life can change and never go back to the way it was.

Amy: That’s a very touching story. When I read the book, honestly, I didn’t realize it was a middle grade reader and I really wonder why it is, because it’s such a beautiful story and it’s quite well-written. And, I just think that anyone can read that and really feel a little bit about Hiroshima. You know, even after the atomic bomb, the American media wasn’t allowed to show photos of it for 30 years. When I came to Japan, when I was 29, that’s really when I learned most about Hiroshima and a lot of my friends were like, oh, but aren’t the Japanese people angry at you because you’re American. We dropped the bomb and of course, Yeah. That’s another perspective without any background at all, about what happened. And you certainly get things on both sides about, oh, it saved so many lives by dropping the bomb because it prevented the war from continuing. But in Japan, the overwhelming majority of people seem to say just that “we were just glad the war was over.” So many people were already suffering and some starving to death, and they just were glad it was over. Where I live is Okayama [prefecture]. I can see Hiroshima [prefecture] from my window across the sea, but not the city. And we also had a couple people here who were in Hiroshima that day and, they were not killed by the blast, but by the radiation poisoning after. Hiroshima, it’s now a thriving city again, but it’s so important that people go and see the photos and the museum and see what really happened on such a large scale and there’s no resentment among the Japanese people. I mean, it was war time and everyone was doing pretty awful things but they’ve moved on. And of course, in the end, Hiroshima ended up being an emblem for peace.

And of course you have been to Hiroshima too, right?

Burkinshaw: Yes. Yes. My mother passed away in January of 2015, and that was only three months after I had got the publishing contract. But so at least she knew it was coming and we were able to honor her in the Peace Memorial Park [in Hiroshima] and have her put onto the Memorial Wall, in June of that year so that was my first time going to Hiroshima. When I was little, I was about eight and my parents and I went [to Japan], but we visited people in Tokyo. At that time, my mother wasn’t ready to deal with going back. So, it was an interesting experience and bittersweet, you know, I was there with my daughter, my husband, standing in the park. And I heard my mother talk about it, and I wrote about it, but when you’re standing there and you see the A-Dome and you just feel, oh my gosh, she was in this area and how awful things she must’ve seen.

And my heart broke, you know, my daughter and I were crying the entire time that we were in Peace Park. We’re so glad we went but you know, one of the things that I realized is how beautiful Hiroshima is. Now in my head, I have been thinking a lot about the bombing, cause that’s what I finished with the draft and everything. But my mom always said when I was younger, that she grew up in a beautiful place. We went to Miyajima Island and we were staying over there and we went to the shrine and my daughter and I, as we’re walking on the sandy path back, we see the mountains, you have the sea and palm trees, which I never expected that there would be.

And, my daughter said to me, we’re seeing it how Grandma saw it, through her eyes. It was the closest that I felt to her, since she had passed away and it’s interesting because with the book, what I really wanted to show was that it was a year before the bomb dropped, because I think a lot of times people don’t know what was happening over there. And they had been at war since 1931 when Japan attacked Manchuria. And so my mom was born in 1932. She didn’t know anything but war. And by the time 1945 came around, there were not that many men left. There were mostly children and elderly people. Hiroshima was no longer that big military port anymore because all the soldiers were out fighting and they had less resources as you were saying. And so they didn’t like the way it ended, but they also thought things were going better because there’s also that propaganda going on, you know, with their own government telling them things. They were just glad that maybe they can start to live again and rebuild. My mom said she was amazed that there wasn’t a lot of resentment.

The book has nothing to do with the political piece of it, because I think, you know, there’s no need to keep arguing why we did it, why we shouldn’t have done it, I think now it’s time to look at it as “it happened.” It was horrific. And it can be so much worse today and we can’t let it happen again.

That’s basically because I feel that both sides of the story can exist. And I think by doing this book was to also show that their culture was different. The things that they were dealing with, their mindset and politics was very different. But the kids like my mom, they still love their parents. They love their friends. They worry what might happen to them. And they wished for peace. This is the same thing that the allied children were thinking and wishing. And so I wanted to show them that the ones that you might think aren’t like you, or are different, or your enemy, that they’re not that different after all, you know, we all have a heart, we all feel emotions. It’s been so rewarding when you’re talking with students and they come up to you afterwards and they say, “I think about nuclear weapons so much differently because I had no idea.”

They just need a connection. You know, the kids in my daughter’s class weren’t being cruel. They didn’t know, they just needed to connect with the humanity under there, you know, and I think in war we focus so much on the awful leaders, or the soldiers, but we forget that there are people, innocent people who ended up getting swept up in this, on all sides, you know, and my mom always said war was hellish for both sides, and I think she kind of showed in a way that she wished for peace because she ended up falling in love with my dad, moving to the United States. My dad was a white American. He was in the Air Force. My mom met him in Tokyo in 1958. And, in 1959 they married at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo and his time was up, and they moved to The States.

Now my mom’s stepmother at that time was not happy with that but you know, my mom fell in love and I just like to tell this little story, but the reason she ended up meeting my father was that my mom was still upset with the Americans, but she wasn’t violent. So her decision was, I am going to date the American soldiers and then break their hearts. And that was her plan.

Amy: Now when you grew up, because you’re second generation Japanese, did you have any kind of cultural affiliation with Japan or did you learn kanji or anything like that?

Burkinshaw: When I was born, my mother had said she Americanized our home. When she came to the States in 1959, she was very shocked that the prejudice that there still was against the Japanese, even though it was 14 years later. She was on the losing side. And so that’s when she started telling people she was from Tokyo and not Hiroshima because she was afraid that would just bring more attention. So she made it her quest to learn more English, which she did. Then she became a citizen before I was born and she wanted to be Americanized. Cause she didn’t want me to go through a lot of the racial slurs that were slung at her, a lot of what she went through. So she sang Japanese songs to me, and she told me Japanese folktales, but in English, and she didn’t really teach a lot to me. And the only time I heard her speaking Japanese was when she spoke to my grandmother, which I thought was so nice to be able to hear it. Unfortunately. I still got a lot of prejudice against me. And I was the only Asian in our school for the first four years. And even then there was only two other people that came and in my neighborhood, I was the only one.

So, it was very difficult for that part of it. And I think, you know, I was very proud that my mom was from Japan. I just found that I can’t talk about it at school so, it was very different in that respect and even going into high school and college, they didn’t have what they have today, where they have all these Japan clubs. You can learn Japanese, even in high school now. My daughter minored in Japanese in college. So I mean, there’s so much more that you can do and so I really didn’t get involved into the culture until I had my own daughter, but before that, when you’re second gen hibakusha, you’re also dealing with, you know, my mom had a lot of PTSD symptoms and issues that she dealt with and she wasn’t going to go talk to somebody.

So she had a lot of times where there was depression where she would sit in the dark for awhile. And I wouldn’t understand cause I was young and I’m just witnessing it and trying to interpret what it is. She had some anger issues and so a lot of that growing up, you just become a fixer and a people pleaser because you don’t understand what’s happening. And because she didn’t tell me about Hiroshima, you know, none of that made sense to me. Of course, as I got older, it started to make more sense and I realized what she was going through, but you’re still kind of going through with her because she was still very scarred.

She didn’t have many outside scars. Her eyebrows never came back in and she had this scar with some glass and stuff in her head still. But other than that, if you looked at her, you really wouldn’t know, but inside, with what she was dealing with and denying of who she was. In the States, when she went to Tokyo, there was still prejudice against hibakusha because they didn’t understand radiation, so she had to pretend to be somebody else. I kind of see her being somebody else and she couldn’t be who she wanted.

She was very sad a lot, and I didn’t know why, and I didn’t know how I could help her, you know? And so I take that with me. And then when I got sick, you know, it’s interesting because then now my daughter’s dealing with, will I have this illness as a result of what my grandmother went through? So she has some issues with trying to work with it all.

And I think it’s so important today that we start realizing with any kind of trauma, that there is multi-generational effects that happen. I didn’t really think much about it until I was writing about what happened, until I started working on the sequel, and until I met someone who does the International Center for Multi-Generational Legacies of Trauma. It’s a big name, but it’s a place in New York city. And they study things, first with Holocaust survivors and their families. Then they study Japanese internment and then their families down the line. And they’re trying to work with people who’ve been involved with nuclear weapons and, nuclear testing because it all does affect each and every generation. And how I wish my mom was here. So I could say, mom, I get it now, you know, I understand this is what was happening. And she probably would have liked to have known, you know, she was feeling something that was normal.

Amy: Can I ask you a little bit about second generation, hibakusha? Now your mother, did she have symptoms also or what we would call radiation disease or, Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy?

Birkenshaw: My mom, when it was a few months after the bombing, that’s when she really had gotten sick and she lost all of her hair on her head, but it did grow back. She did not get sick again. She was very blessed until she was in her eighties when she did end up having cancer, but when I was born, there was a lot of issues with my immune system.

And so doctors knew that that was part of the issue. I got sick all the time as a child. And so when I got into the hospital in my thirties, I originally had a blood clot. And it caused some damage in my leg to the nerves and because of my immune deficiency, it opened me up to an autoimmune disease and this particular disease deals with any kind of nerve damage.

My mom, even though she wasn’t physically sick all the time, she lived in constant fear of being sick and dying. And I didn’t understand growing up until later, but she would always say every time she didn’t feel well, “Oh, that’s it I’m going to get cancer.” She just was waiting for it to hit her.

Amy: I think there are many second generation hibakusha then.

Birkenshaw: Yes. And I have had the opportunity to finally meet some and they’re not all physically sick. But they all have experienced the emotions and the psychological issues of their parent.

I find it’s very different too, because. I grew up on the east coast of the United States. Not a lot of Asian people. I was also mixed. My dad was a white American. My mom was Japanese, so they weren’t both dealing with it. And we were living in the place, you know, where, the war went between. So you still didn’t hear very much about it on that end.

I know someone who grew up on the Pacific side of the United States. Now there was a heavy Japanese population, there was even a large Japanese hibakusha population that moved there after the war. So she was around it a little bit more, and then another person that I met, she grew up in Hiroshima, which was very different. Also the way that they read books in school, they read Barefoot Gen. And it was so frightening to them because they kept thinking, oh my gosh, we’re going to get sick. This is what’s going to happen to us. And so it’s such an interesting way of how, if it’s not physically affecting you, and maybe if I didn’t get the blood clot, but I have some now some circulation and blood issues, which they also go back to, because my system is not made the same from what happened. I’m hoping that with my daughter, that she doesn’t get anything physical. My husband is also a white American, so I’m hoping that maybe as we go, she’s only a quarter [Japanese] now, so maybe she won’t have any issues with it, but I know she worries every time if she injures herself, you know, is it going to turn into something?

And she had to really help me a lot when she was growing up. So it kind of changed the whole dynamics of everything. So I really feel that any second generation hibakusha, there’s something that it affected the way that they grew up or the, you know, the way that their parents were, whether they talked about it or not. There’s still a lot of people who will say that their parents never talked about it at all.

Amy: And people talk about stigmas and such. But you know, even when we [Japan] had the Fukushima incident with the leaking of a nuclear power plant after the earthquake in 2011, suddenly, everywhere in the world people were like, oh, Is it going to affect us? And, oh, can you eat the fish? So stigma is actually a natural thing. People tend to think of it as being something specific to Japanese or to certain other cultures, but they just don’t recognize it in their own culture. Same thing with taboo subjects, right? You know, in America we think we can talk about anything, but actually there’s a whole host of things that are taboo to talk about. But if it’s your own culture, you don’t think of it that way.

So, I wanted to ask you about writing your book. It’s historical fiction. And it’s your mother’s story, told in the first person. And I guess based on the real people, since you talked about her best friend, Machiko. How in the world does one go about writing a book like this? To get all the experience needed and the historical facts and the research. I mean, you’re living in America, right? So it’s not like you can just run over to the Hiroshima Peace Museum and get some facts. So can you, let us in a little bit on that?

Burkinshaw: It was difficult because I wanted to do a lot of research first because I wanted to make sure if I talked about Japanese life, that these things existed, or this is how it went. I had what my mom told me, but I couldn’t just go by that. And so trying to find sources that are translated into English about daily life in Japan. Now I did get lucky with eBay because some libraries were weeding their books and there happened to be a few sources Daily Life in Wartime Japan was one of them. I can’t think of the others, but they had a few that were actually translated. I use some of the internet. But It wasn’t as big as it would be now that I’m using it for the second book. But, and so I spent a lot of time on World War Two and what it was like then and I also used another book which was, A Boy called H written by a Kappa Senoh and that helped a lot. And so I would ask my mom, well, okay, I read this, so how was it at your house? And she’d explain it. Then I knew I only had a year to put what happened and the events in the book. I’m not going to say what they were, but they were really family issues that happened. The timing of stuff was a little bit different but, she dealt with a big blow about her family a little bit before the bomb had hit. And it took me quite a long time also because I’m trying to picture my mom as a 12 year old. And I think we all have trouble picturing parents being younger. If I was 12, how would I react to it? And, you know, because the protagonist is 12 years old, that’s where the publishers go. Okay, so it’s gotta be a middle grade, which it doesn’t make a lot of sense of how that all works.

And like you said, I’ve had older people read it, people in college use it in class, but I really wanted to make it flow so that the reader could kind of follow what her life was like and kind of feel her, her inner thoughts, which is why I wanted it to be in first person and, and her struggle and to show that she had, you know, she didn’t like to do homework. She never kept a room clean. She and her cousin didn’t get along and they used to argue, but then she had these fun times with her best friend and they could listen to jazz music. And so the events, especially on August 6th and afterwards, is what my mother told me.

And, a lot of what happened in between is also what she told me, but of course you kind of change the circumstances but, when I had to do the difficult pieces, those chapters and I had to ask my mother. You know again. To try to describe it I would read other books so I could read other descriptions, but then I’d have to end it with, okay, well, let’s talk about, you know, describe your house to me, just so I could get something from that to make her happy again.

When I was writing it, when it was really difficult with those scenes, I had to take like a week or two off and just do absolutely nothing because it wore me out. And I started dreaming about it as if it was me there. And I’m hoping in some way, maybe that helped to be able to give a good description of how it was because I felt that to get this book out there in this story, I wanted to be so sure that it would resonate with people somehow, and it wasn’t just another telling of what happened. It wasn’t a white lens. It wasn’t a Japanese lens. It was a 12 year old little girl lens. It took me, you know, about five years between the research and writing it and then getting an agent and submitting and then more edits and, you know, building upon that.

Amy: Well, I think you should be very proud of what you’ve produced. This leads us into what your favorite books on Japan or Asia are. We like to ask everyone at the end of the podcast, what their three favorite books are.

Burkinshaw: One of the ones is a newer one that I’ve read is Kokeshi: from Tohoku with Love by, Manami Okazaki. It talks about how she goes to these different areas in that region and the kokeshi doll, how they came about the different styles. And I have three of them of my own that my mom had had forever. So it was very interesting to read.

The other one I read a while ago and it’s called Ash by, Holly Thompson. And, it really introduced me how someone who’s not Japanese, but can be in Japan and still learn the culture and what happens so I found that book to be very good.

And then the last one, and it’s interesting, cause you mentioned Fukushima, is Up From The Sea by Leza Lowitz. She writes it beautifully in verse. And it talks about what happened in Fukushima with the earthquake and the tsunami, and then how they deal with it emotionally. And I thought, oh my gosh, you know, it’s, it’s different, but it’s also kind of the same and how the feelings were in things just swept away and how she could meld it also with what happened in the States and 9-11. I just thought she wrote it so beautifully.

Kathleen Burkinshaw is the author of The Last Cherry Blossom Visit her website or her Blog Creating Through the Pain. You’ll also find her on the following social media outlets:

The Last Cherry Blossom will be translated into Japanese and published by Holp Shuppan in 2022.