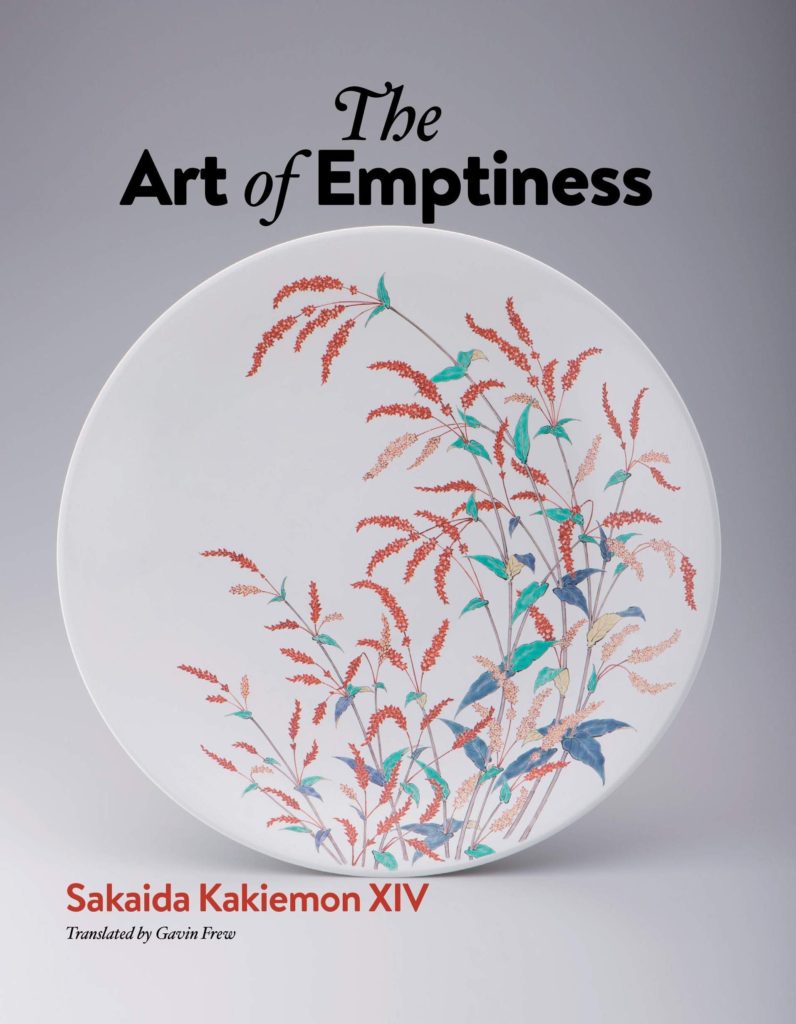

The Art of Emptiness gives the reader insight into one of the most famous lineages of Japanese pottery. Interviewer Watada Susumu starts off with a seeming digression: Kakiemon—the fourteenth generation heir to the famous Japanese pottery tradition—gives a detailed and insightful description of how to smoke a pipe. The charismatic Sakaida Kakiemon XIV, who gave up his birth name “Masashi” after his father (the thirteenth Kakiemon) passed away in 1982, is fascinated by the “flow and rhythm” of pipe-smoking. He reveals tricks for cleaning the bowl and how to flip the tobacco to get an even burn. He bemoans the withering production and supply of shredded pipe tobacco. To Kakiemon, smoking is not just a considered pastime: “Smoking is part of the job.” What seems an irrelevant digression is actually a portrait of a master craftsman, and of the attention to detail that Kakiemon brings to everything he does with his hands.

The Art of Emptiness is a collection of interviews with Kakiemon XIV over a three year period. Originally published in 2004, this English translation by Gavin Frew was released in 2019, six years after the death of Kakiemon XIV (his son Hiroshi has since succeeded him as the fifteenth Kakiemon). In the conversational tone of the book Kakiemon XIV comes across as a humble, jovial fellow, laughing his way through a recounting of his upbringing in the kiln under the supervision of his laid back father, and his demanding grandfather. The book is a window into the formation of someone predestined to be a master craftsman and take the mantle of a four-hundred-year legacy.

The middle third of the book covers the end-to-end production process of porcelain works. Although filled with detail, the book keeps a brisk pace. It is particularly interesting to learn what has changed over the past four hundred years.

Each successive heir to the Kakiemon lineage must contend with tensions between tradition and transmission, of being a craftsperson versus an artist, while having a deep-felt responsibility to properly run the business of the kiln and keep workers employed. Changes to the land over the centuries also affect production. Over and over Kakiemon XIV laments how the raw materials used in pottery have changed. The ash of the winter hazel tree is a key component of the ceramic glaze but due to declining numbers of the tree, the Kakiemon family is forced to uproot its tea fields to plant winter hazel thereby protecting future generations of potters. A Kakiemon must always think about the future while looking at the past.

The final section, “Appreciation”, covers a series of case studies. Accompanied by full colour photos of pieces, Kakiemon XIV demonstrates the key characteristics of his tradition. Aka-e is the distinctive enamel colouring used in the paintings. Nigoshide, a term from the Arita dialect meaning “water that rice has been washed in,” is the milky-white surface that Kakiemon works are known for. Finally, there is yohaku, the blank space representing “emptiness”, a philosophical theme that permeates the book.

The pottery techniques of Kakiemon have been designated an “Important Intangible Cultural Property” by the Japanese government. The story of the first “Kakiemon the Potter” has even been captured in Japanese elementary school textbooks. The Art of Emptiness brings the legacy of Kakiemon to English readers in an accessible manner, directly from a lineage successor once designated a “Living Treasure.”