Reviewed by Chad Kohalyk

One day in 1985, from the hills of Kunar province in northeastern Afghanistan, came three women dressed in chador, their faces covered. The two sisters and their mother were victims of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and had come to the hospital ward of Nakamura Tetsu, a volunteer doctor from Fukuoka Japan and a specialist in treating Hansen’s Disease (leprosy). Removing their niqab, the younger sister “had a cavity where the bridge of her nose should have been” and the older sibling was completely bald. The mother had a burn on her foot which was necrotizing. The younger sister, Harima, pleaded for death. Meanwhile, the Soviet army was pushing up the valley getting closer every day. But Dr. Nakamura’s immense determination allowed him to press on with treatment for months among the chaos, even through his own self-doubt: “I, too, was just another lowly, confused human being, living awash in the mud of life along with our patients.”

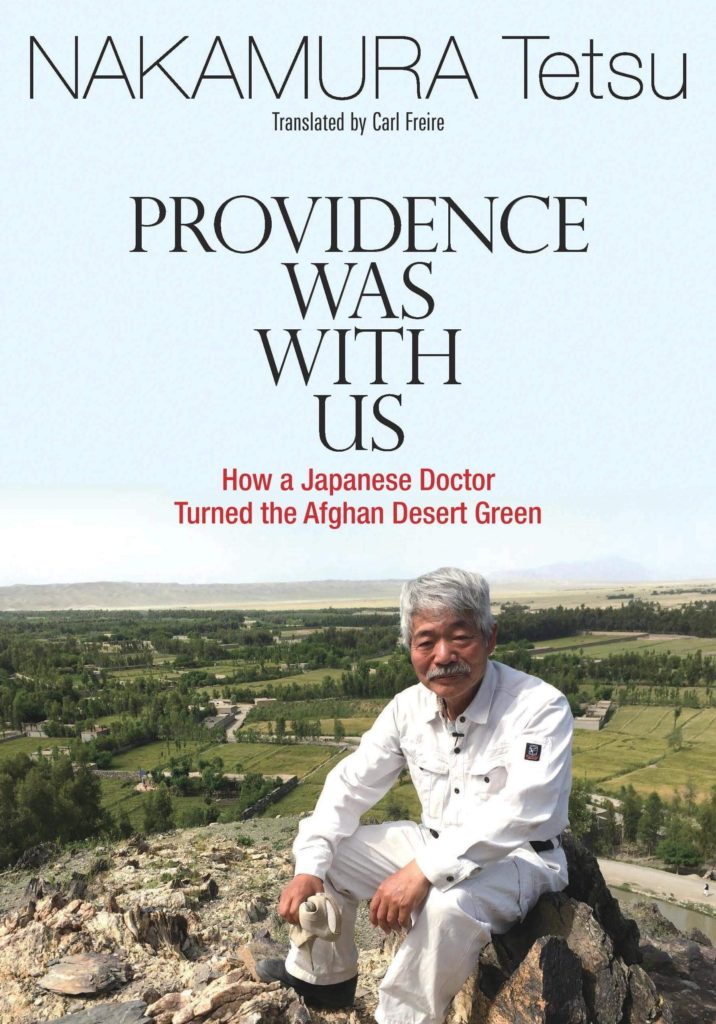

Providence Was With Us: How a Japanese Doctor Turned the Afghan Desert Green (translated by Carl Freire) is Nakamura Tetsu’s account of his thirty-five years as a volunteer in the nebulous border regions of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Nakamura was an internationally decorated aid worker who started his humanitarian work helping patients one-by-one in a Pakistani hospital. He aspired to maximize his impact by building clinics, delivering food aid and digging over 1600 wells. He further constructed mosques and madrassas for local communities. His titular accomplishment was the irrigation of a twenty-five kilometer long canal, reclaiming desert to turn into farmland thus impacting the lives of over six hundred and fifty-thousand people.

“One irrigation canal serves the community more than 100 clinics.”

— Nakamura Tetsu

In all these endeavors there were many hardships, too many for a two hundred-page book to cover:

“We went through seven years truly on only spirit and willpower. Natural disasters in the form of great floods and concentrated local downpours on a scale not seen for several centuries were not the only problems. We also faced human-caused troubles, such as mistaken attacks on the wrong targets by US forces, sabotage by local warlords, anti-American violence, desertions by engineers, betrayals, robberies, malfeasance by staff, internal conflicts, struggle with people living on the opposite bank, disputes with landholders…the list was endless.”

Dr. Nakamura possessed an incredible determination, but also an adept pragmatism. The first chapter covers his upbringing in post-war Fukuoka, scraping together a living with hard-drinking parents who operated in the grey parts of society. His uncle, a famous writer and propagandist for the war effort, unable to reconcile his ideals with the results of the war, ended up committing suicide. These extreme experiences seem to have contributed to the doctor’s ability to navigate the complex tribal politics in Afghanistan and stay alive for so long. He points out “[i]t is normal for foreign armies to be uncertain who is their enemy or their friend and to become gnawed by suspicion and doubt” while adding “foreign aid organizations are also affected by it.” How systems and ideologies let people down is a common theme throughout the book. Providence Was With Us provides an unvarnished view of an aid organization that has been on the ground for the long term, and has operated through two foreign invasions, massive drought, and the aftermath of such crises. Other NGOs came and went, but Nakamura’s Peace Japan Medical Services, aka the Peshawar-kai, stayed. At one point he was forced to close most of his clinics, not due to war or drought, but interference from foreign NGO bureaucrats and their ignorance of conditions on the ground.

Treating leprosy patients while under threat of invasion from the Soviet Army, a letter from Tokyo arrived. It was a request for the doctor to share his experiences: “Let us have a conversation in an Asian mountain village surrounded by its people and the beauties of nature.” Nakamura had little time for high-minded internationalism, focusing rather on practical problems such as boulders too large to jackhammer while digging wells. A keen listener, he relied on local knowledge and skills in the application of “unexploded rocket shells and landmines” to blast them. When he did go back to Japan to speak at official functions, he brought a simple anti-war message, inconvenient for Japanese politicians keen on using the US-led invasion of Afghanistan to transform Japan’s overseas military capabilities. Determination and pragmatism, combined with the virtue of listening carefully to both local needs and local knowledge, allowed Dr. Nakamura to have an outsized impact and become a beloved hero in both Afghanistan and Japan.

Nakamura Tetsu was murdered on 4 December 2019 in Jalalabad, shot to death with five companions in a targeted attack by unidentified assailants. A state funeral was held for him in Afghanistan; 1300 mourners attended his funeral in Fukuoka. Released one year after his death, this translation of his final book (Japanese title Ten to Tomo ni) is an important step to bring Nakamura Tetsu’s legacy to a wider audience. It is only the second of his dozen books translated into English,the first being a practical guide to canals that was also translated into Dari and Pashto.

Providence Was With Us is a short memoir of specific projects in the field, not an autobiography. Nakamura is telling us the “what” and “how.” For him, the “why” was self-evident. Yet the book gives tantalizing hints of action off-screen, making the reader want to learn more about his life and philosophy. He barely mentions his wife and five children whom he left in Japan. According to Yatsu Kenji, a documentarian who filmed Nakamura for over twenty years, he was well read and a

deep thinker. There is much more to explore about this remarkable man’s life. What better than to begin with this account of his deeds.

Notes:

The reviewer visited one of the sites in the book in Fukuoka and uploaded a Twitter video. (@chadkoh)

The original Japanese version of the book is available here.