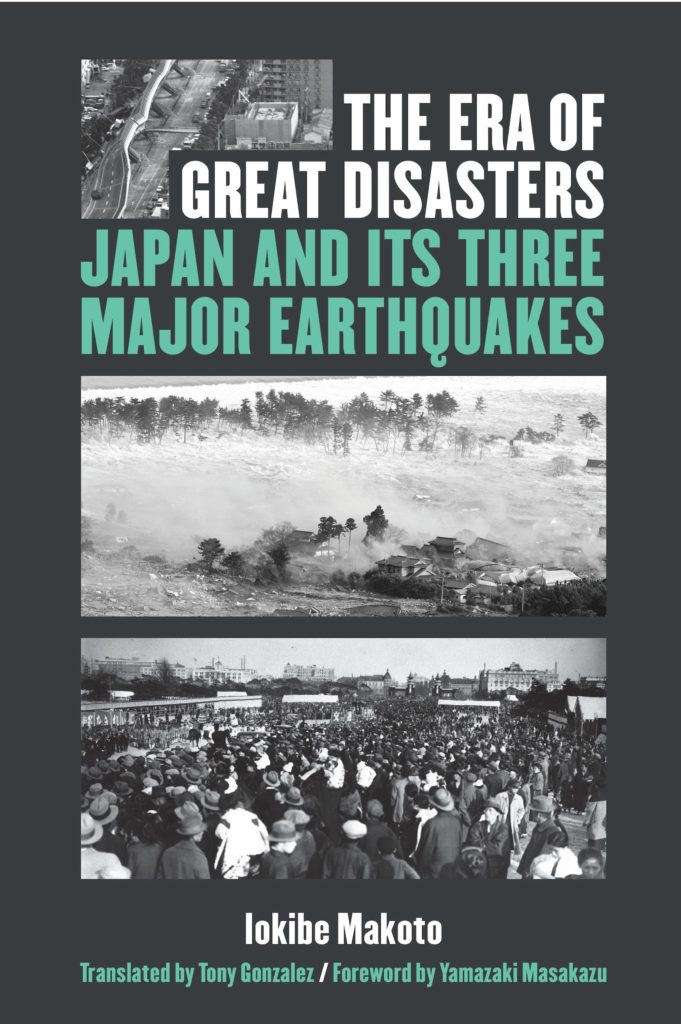

The Era of Great Disasters: Japan and Its Three Major Earth Quakes, by Iokibe Makoto (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies, July 2020)

Review by Amy Chavez

Included in the University of Michigan Press ‘Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies,’ The Era of Great Disasters is a scholarly but highly readable text that investigates Japan’s three major quakes: The Great Kantō Earthquake (Yokohama, 1923), The Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake (Kobe, 1995) and the Great East Japan Earthquake (Tohoku, 2011). The play-by-play telling of each event, from the first rumbles and unfolding of the disasters to first responders sometimes reads like a thriller complete with insurmountable dilemmas among impeccable timing. The author, himself a victim of the 1995 disaster takes the reader behind the scenes into the Prime Minister’s office and board rooms of government agencies to parse the catastrophes from beginning to end, including recovery efforts and reconstruction of beleaguered cities.

The book sheds a welcome light on the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923 with its epicenter in Yokohama, that killed 105,000 people, 90 percent of them casualties from the resulting fires that spread through Edo (Tokyo). Iokibe expounds upon the “Vigilante Massacres,” in which hundreds of Koreans were randomly killed after false rumors circulated that Koreans were looting, murdering and starting the blazes. Conscious steps were taken to make sure such events didn’t repeat themselves in the future.

Among the myriad details the text presents, two really stood out for this reader. The first is that researchers tied higher survival rates to those living in communities that held local festivals. Because residents had close ties, they had a vested interest in helping each other. Because they visited each other’s homes often, they were familiar with the layout of houses and were better able to rescue their neighbors. The second item was how students in a dormitory at Kobe University of Mercantile Marine rescued Kobe residents under the direction of one particular student, Arita Toshiaki, who took charge by insisting his dormitory mates don gloves, boots and winter jackets before rushing out to help people in dire need. He further instructed them to first visit houses that hadn’t collapsed in order to borrow tools such as saws, hammers and crowbars. Arita’s foresight enabled the Hakuō dormitory students to work quickly and efficiently to rescue over 100 people in their neighborhood.

The last third of the book is dedicated to mitigation. Disaster preparations and regulations are changing on national, prefectural and local levels as Japan looks to prepare for future calamities. The Sanriku area in Eastern Japan has been repeatedly devastated by tsunami in the Meiji, Showa and Heisei eras. Of the 22,000 lost lives in the East Japan Earthquake, 90 percent were a result of the tsunami. This has prompted towns to move or rebuild at higher elevations, construct higher sea walls, and relocate individual houses. The nation’s 2.1 percent tax increase to cover the costs of the devastation is also unprecedented.

Discussion is also given to reconstructing cities, and given Japan’s shrinking population and continuing depopulation of the countryside, how to rebuild. Should some towns be replaced at all? If so, should they be rebuilt with just the necessities, or enhanced for future generations?

The author is president of the Hyogo Earthquake Memorial 21st Century Research Institute and penned a regular column on natural disasters for the Mainichi newspaper.