Books on Asia interviews Danica Davidson and Rena Saiya about the two manga books they’ve created together

Danica Davidson lives in the USA. Her articles on manga have been published in CNN, MTV, Publisher’s Weekly, Booklist, Otaku USA, and Anime News Network. She has also edited English adaptations of Japanese manga. She has co-authored with Rena Saiya Manga Art for Everyone: A Step-by-Step Guide to Create Amazing Drawings; and Chalk Art Manga: A Step-By-Step Guide.

Danica Davidson lives in the USA. Her articles on manga have been published in CNN, MTV, Publisher’s Weekly, Booklist, Otaku USA, and Anime News Network. She has also edited English adaptations of Japanese manga. She has co-authored with Rena Saiya Manga Art for Everyone: A Step-by-Step Guide to Create Amazing Drawings; and Chalk Art Manga: A Step-By-Step Guide.

Rena Saiya lives in Tokyo. She is a manga author who has worked on 12 books with the Japanese publisher Shogakukan.She is co-author, with Danica Davidson, of Manga Art for Everyone: A Step-by-Step Guide to Create Amazing Drawings; and Chalk Art Manga: A Step-By-Step Guide.

Rena Saiya lives in Tokyo. She is a manga author who has worked on 12 books with the Japanese publisher Shogakukan.She is co-author, with Danica Davidson, of Manga Art for Everyone: A Step-by-Step Guide to Create Amazing Drawings; and Chalk Art Manga: A Step-By-Step Guide.

Books On Asia: Danica and Rena, you have made it your mission to share your love for manga: reading, writing, drawing and experiencing it. Could you help your audience differentiate between a manga artist, a manga author, a manga illustrator and a manga creator? What should we be calling you?

Danica Davidson: I just do writing, so I’m a manga author, but Rena writes and draws so she could be called a manga-ka, a manga creator, a manga illustrator and a manga author. In American comics, you often have one person doing the writing and another person doing the art.

Rena Saiya: And in Japan, usually one manga creator does both writing and drawing.

BOA: So, when Japanese manga is translated into English, do they translate just the text and keep the same drawings?

Danica: Basically. I got involved in manga adaptation, in which they would have someone translate the Japanese words into English but it would come across very literal, so they would have me come in and write it more like how teenagers talk in English, because the books I was working on were aimed at teenagers.

BOA: Were those original scripts you worked on? Or adaptations of classic literature and novels, for example.

Danica: They were all original stories. I did one called Millenium Prime Minister, about a girl getting engaged with the Japanese Prime Minister.

BOA: How did you two hook up for Manga Art for Everyone and Chalk Art Manga?

Rena: Danica contacted me over LinkedIn.

Danica: I had been writing about manga and anime for quite a few places, and Skyhorse Publishing approached me about doing a manga art book. They told me to find an artist, so I was trying to find someone in Japan. I eventually found Rena on LinkedIn and saw that she was a professional manga-ka, she spoke English, and she was interested in publishing abroad.

Rena: I was interested in her proposal, but of course, I had a lot of questions. We’ve never met in person but we talk through Skype and email.

BOA: How did Chalk Art Manga come about?

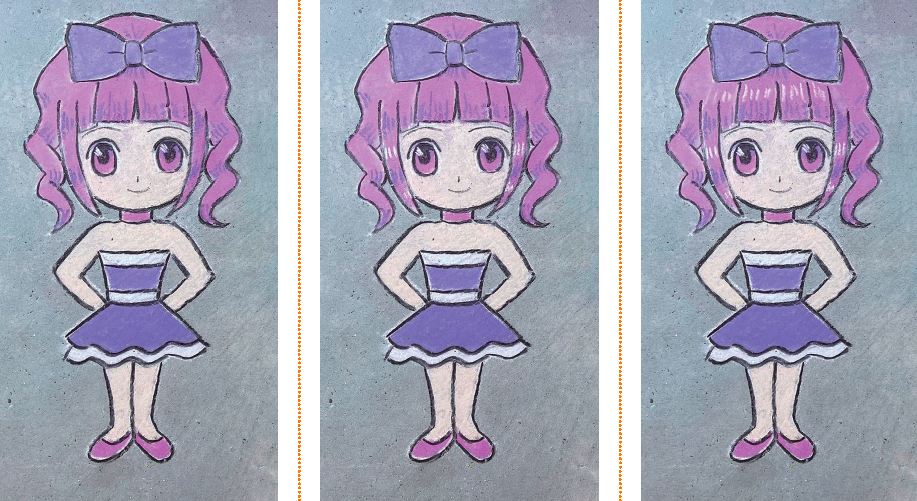

Danica: One of the editors at Skyhorse asked me what I thought about doing a book on chalk art, but in the manga style. I thought, “Why hasn’t anyone thought of this before?” Lots of American kids grew up doing chalk art, and they love manga, so it’s a great combination. I’ve seen people doing manga style chalk art at anime conventions, but not beyond that. One of the cool things about chalk art is that it is so colorful. Manga tends to be in black and white so I thought that color would get these manga style characters to really pop.

BOA: It seems like most students in Japan can draw manga. If you walk into a junior high or high school classroom in the morning, for example, the entire chalkboard will be covered in manga drawings. The students doodle all day long and it seems like something everyone can do. Enter the Chalk Art Manga book. It shows that manga is something anyone can do because you explain it step by step, starting out with really simple stuff, like a heart, how to color it in, and how to smear the the chalk with your fingers. What is your market with Chalk Art Manga?

Danica: I figured it was something that would interest kids through adults. I wanted to introduce simple things that kids and beginning artists can do. But then you can get more complex or, if you’re already an artist, you can just follow the steps to learn how to make all these characters.

BOA: Can you tell us about the original journey of the book, from Manga Art for Beginners to Manga Art for Intermediates, to Manga Art for Everyone?

Danica: Manga Art for Beginners was the very first book. It starts with a step-by-step guide to drawing eyes and anatomy and then the characters themselves. Manga Art for Intermediates became Manga Art for Everyone. It’s basically the sequel to Manga Art for Beginners. Manga Art for Everyone shows step-by-step but we don’t show the eyes and anatomy.

Thanks to Rena’s input, it includes information on how Japanese creators put on screen tone, how to make the hair shine, what software to use, what pens they use, etc. As far as I know, there is no other book in English that tells you those things.

BOA: That brings up some interesting points about the differences between manga in the US and manga in Japan. Light, sound, suggestions of color. How do you get across feelings, emotions or the general atmosphere?

Rena: Sometimes in Japan we use background to show feelings. So there is no landscape then. Via the background, you can sense complex feelings, for example, that the person is angry, sad, anxious, pleased, etc. Any kind of feelings can be expressed or emphasized by such backgrounds. It’s not easy to explain what they look like, but you can see the indicators in the background when there is no landscape or other objects in them. For example, they could be cloud-like abstract patterns or saturated lineworks.

BOA: How much has Japanese manga influenced American comics?

Danica: American comics is a really big industry. The superhero comics of DC and Marvel are best known but there are a lot of indie comics. Kids comics are becoming really popular. There is definitely influence from manga. I think it’s a combination of people who really love manga and they want to use that style, and there are people who see that manga is selling really well and they see dollar signs and want to copy it and get in on the popularity of manga. I definitely see a lot of stuff that looks like it’s American comics and Japanese manga mixed together. And I think especially with some of our How-to-Draw books in America, that’s what they look like. So that’s something I thought about a lot and worked on to make sure our books really did look like Japanese manga.

BOA: Are most people aware of manga now in the US?

Danica: I think it’s generational. People who grew up in the 90’s and after all grew up with it. Astro Boy and Mighty Atom came to America. We had Robotech in the 80’s and it’s been building over time. It seems like everyone is getting into it now with the younger kids in schools. Professional athletes have grown up with manga now and celebrities say they love anime and manga.

BOA: About ten years ago there started an influx of tourists who had come to Japan for the sole reason that they were familiar with Japan via manga and wanted to see the locations of anime films. Especially French tourists were very familiar with manga.

Danica: France is a huge market for manga and they have a long history of comics, which are more mainstream in France. You’ll see the French president tweeting about manga, so I think that’s pretty cool.

BOA: Rena, as a Japanese person, what stands out to you as a major difference between publishing manga in Japan and manga abroad?

Rena: As for the word manga, strictly speaking, when people use the word “manga” in a foreign country, usually it would refer to Japanese manga which are translated into the country’s language. So the counterpart of manga in a foreign country should be called comics except when the creators of the comics really try to follow Japanese manga style.

Though I don’t know so much about publishing comics abroad, in the case of America and France, they already have traditional comics. In America, it seems that in general, comics are created by a team in a division of labor using story creators, storyboard creators, sketch drawers, people who do inking, people who do coloring, etc. They work together to make comics while in many cases, a Japanese manga creator does everything by himself or herself except when he or she needs to meet deadlines, in which case assistants are hired just to help finishing the illustrations in the panels. So, usually Japanese manga is very personal work.

In France, traditional comics are called bande dessinée and they are regarded as a kind of art, while in Japan manga is thought to be entertainment. Therefore, I’ve heard that finishing bande dessinée books takes much longer than Japanese manga books even when the number of pages is the same. I think it’s because they are trying to create perfect art books to the best of their ability.

BOA: Lastly, please share with our readers your three favorite manga books on Japan.

Danica: Only three? If I had to break it down, I’d say Descendants of Darkness, Death Note, and Phoenix, the latter of which is, unfortunately, out of print in America.

Rena: I’d have to say Glass Mask, a series which has been running for over 40 years, Phoenix, and Black Jack, the latter two by Osamu Tezuka, the father of the modern manga Industry in Japan.

Visit Rena Saiya online:

Website: www.japanese-manga-artist.com

LinkedIn: Rena Saiya

Visit Danica Davidson Online:

Website: www.danicadavidson.com

LinkedIn: Danica Davidson

Twitter: @danicadavidson